Designing Cinematic Lighting

What does it take to design lighting that feels real, serves the story, and still works under brutal production pressure? In this episode we'll learn how observation and language drive fast, reliable choices. You’ll learn to separate daylight into its actual sources, understand why popular “systems” aren’t cinematic shortcuts, and hear how professionals really use terms like key, fill, and contrast ratio to communicate under time constraints. Along the way, we tackle today’s biggest lighting questions: When should realism dictate your choices, and when should you bend it? How do blocking, look, and motivation stay in sync without slowing the shoot? And how can a small shift in lighting cue tension, imply time, or quietly steer attention?

This is a transcript from Visium: The Secret Language of Images. Listen to the episode below:

Some years ago, I was on set filming a movie in Vietnam. This was a comedy, and the schedule was packed. We rushed from one location to another, doing our very best to finish days on time and get all the footage the director needs. If you’re an experienced filmmaker then you know, on set the schedule is the most important thing. And small problems tend to quickly become big ones if they cause even a slight delay.

In one particular day, we were about to wrap the day when the editor called to tell the director of a problem. Smart filmmakers start editing the film while its still being shot, because when you’re on set it’s relatively easy to squeeze in another shot. But once you’re done, getting that shot becomes the most difficult thing in the world.

Screengrab from De Hoi Tinh, directed by Charlie Nguyen and behind the scene image

The editor had an issue with a transition between scenes and a plot point that wasn’t entirely clear. He suggested that we quickly film the two main character running around in the street looking for a third character who has gone missing. Sounds simple enough, right? The only problem was that this scene was supposed to take pace during the day. It was already night, it was raining, and we were leaving to the countryside the next morning.

The producer looked at me. Can you create a day exterior scene, block the rain somehow and shoot this thing in 30 minutes? Like any ambitious cinematographer, I said yes first and worried about how later on.

Recreating daylight at night is not a technical problem. In the last episode we talked about the most important aspects of lighting: observation and language. So imagine yourself standing in a street corner during the day. Where’s the light coming from, and what is its quality? The difficulty in doing this exercise is that there’s actually more than one light source in a normal day situation. There’s the sun, but when the sun is not hitting the subject directly, it lights it indirectly through reflections from buildings, the ground and of course the biggest, softest light source we have - the sky. When thinking of daylight we have to separate all these different light sources so we can recreate daylight in a believable way - or to emulate it. Emulation is an important lighting word.

When I work with students in a studio and ask them to try and create daylight coming in through a window, they usually start by placing a lamp outside of the window as if it’s the sun. It makes sense, but it never looks believable. The difficulty is not related to lamps, it’s about understanding the quality of each light source. Once you know that, you’ll also be able to tell which lamp to choose.

So in Vietnam, I needed to recreate daylight outside, even though it was dark and rainy. I had flexibility with season and whether, the director just needed to get it done. So I decided to make it easy for the crew and myself - an overcast day, where the main light source is just the sky. We used all our largest frames with white fabric overhead, and bounced pretty much all of the lamps we had off the white reflector overhead. The result was a soft, even light coming from above, and as a bonus the frames also provided cover from the rain. This provided for a large enough area to use a wide lens, and that was it. The audience couldn’t tell.

This might sound extraordinary to inexperienced filmmakers, but if you’ve been making movies for a while then you have a story like this too. Filmmaking is a constant act of problem solving. When it comes to lighting, emulation begins with careful observation of every day light, and categorizing it in our heads using language. This was the only way I could quickly figure out how daylight looks like without using visual references, relying only on my experience and observation.

I’m Tal Lazar, and this is Visium—where we explore images and figure out what makes them work. In this first series, we’re focusing on the images you see in movies.

Who said you can’t learn lighting in a podcast? We’ve already covered some of the most important aspects of lighting, mainly its qualities and emulation. It’s true that as long it’s all in theory you are not really lighting, but remember that even if you’re not physically moving lamps you’re still designing. Choices like locations, time of day, or weather all affect lighting, and a director can easily participate in a non-technical conversation about lighting, looking at visual references to decide how lighting contributes to visual storytelling.

This is where we should mention something very important. If you look up cinematic lighting techniques online, you’ll find many guides and how-to videos. You’d learn about stuff like the three point lighting system or eye-lights, as if these are the methods professional cinematographers use to make their scenes look cinematic. I’ll say it in the most simple and direct way: this is a lie.

Lighting design begins when the screenwriter writes something like, interior night. A cinematographer reading that line immediately wonders where the light is coming from.

The concepts of key light, back light and fill light are important to know, but not for the reasons you might think. The idea that there is a technique to master that would just make an image appear cinematic should be insulting to directors and cinematographers alike. Think of some very successful films like Blair Witch Project, Napoleon Dynamite or the Dogme 95 films. You won’t find a lot of backlight there. The idea that there’s a shortcut to cinematic storytelling, that you can follow a convention and make the audience feel something and be interested, is just wrong.

The Three Point Lighting System

Sure, if you make something look like a movie, like my students say, you might catch the audience’s attention for a moment. But to keep them interested for the duration, you’ll actually need to tell a good story. So I suggest that you abandon the idea that lighting conventions are a path to learning cinematic lighting, and instead focus on what we talked about last episode. Observe lighting in reality and in movies, especially when you feel that it’s effective in making a moment powerful. Break it down using the basic qualities, and try to use it in your own scene.

But lighting conventions like the three point lighting can still be useful. If you’re not familiar with three point lighting, just look it up. Most of the lighting videos on YouTube teach you how to do it, because it’s much easier to teach a technical aspect of lighting than teaching people how to observe and remember. If lighting was so easy, all movies would look like a million dollars, right?

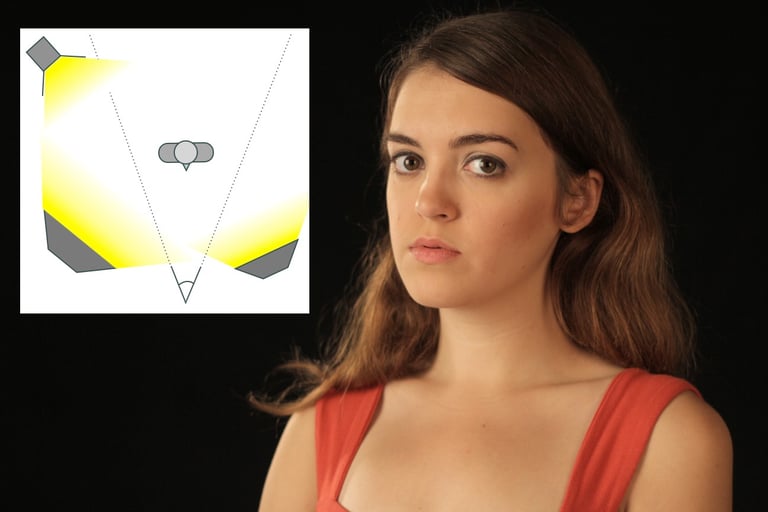

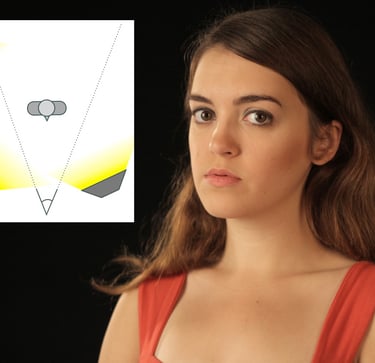

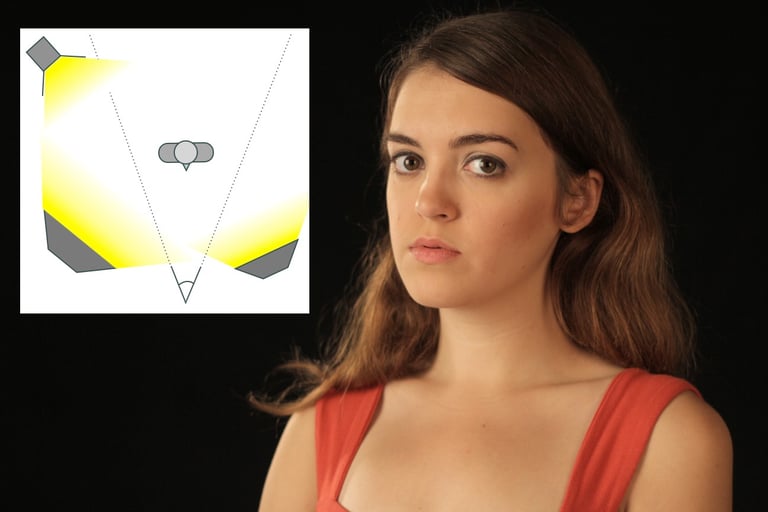

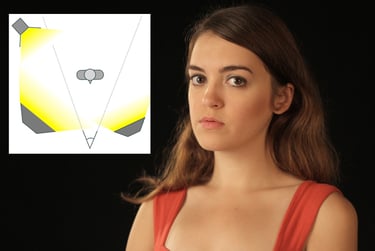

So how can these conventions still be useful? As a language. If you’ve ever been on a professional set, you heard the words key light, or fill light, endless times. That’s how the film crew communicates efficiently. A cinematographer might tell the gaffer that the contrast ratio is too high, and that more fill is needed. Contrast ratio is the relationship between the dark and bright side of the face. A 2:1 contrast ratio means that one side of the face is twice as bright than the other side. Adding fill means making the dark side brighter and reducing the contrast. But saying this means nothing about how it should usually be done, it’s just a form of communication.

The Blair Witch Project, directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez

Cinematographers and their crew speak in terms of key light, back light, fill light, foreground, background, separation and many other terms that all originate in conventions. Knowing these terms can help a director communicate as well, but no one should confuse these conventions with textbook methods to achieve storytelling effects. That requires context, which the story and the people working on it create.

Lighting design begins when the screenwriter writes something like, interior night. A cinematographer reading that line immediately wonders where the light is coming from. That question is rooted in a convention too, but a deeper one than three point lighting. You see, in the old days, filmmakers were not as concerned with the motivation behind lighting, where it comes from in the world of the movie. Old Hollywood movies, especially in the golden era, nurtured the image of its stars. Look at old movie still of Marlene Deitrich or Katharine Hepburn and you’ll see something interesting. No matter the scene, it could be in a dark cave in front of a firelight on the ground, and the light in a close-up would be a spot light from above, like a theater light. Maintaining the image of the star was more important than realistic lighting.

Contrast ratio is the ratio between the bright and dark side of the face

Today things are a bit different. The most terrifying thing for a young filmmaker is distracting their audience and reminding them that they are watching a movie. So every choice must be motivated by something within the fictional world, even lighting. That’s why cinematographers begin designing lighting by looking at the world. If it’s a night interior, then are there table lamps? Ceiling lamps? Candles? And if nothing, is there a window where moonlight can come in from? Lighting must have a reason to exist in modern conventional lighting, and if it doesn’t then there better be a good reason.

This convention is also a source of trouble, and why young filmmakers struggle on set with blocking. Not every angle looks good, and without understanding of lighting, actors and directors block scenes in a way that can make it difficult for an inexperienced cinematographer. Add to that a bit of insecurity and poor communication skills, and you got yourself a conflict.

So let’s try to settle this thing. First of all, it’s true that modern lighting conventions call for a sense of realism, but this is actually something a director and cinematographer should discuss in pre-production. Maintaining such strict realism while keeping a certain look means there are limitations in blocking the director should be aware of. More flexibility in blocking means also being a bit more flexible with the look, or developing it into something else. It’s really all part of the same thing, the style of the director is part of the storytelling.

Another interesting side to this expectation for realism is that it can very much be used in a creative way. Yes, the audience expects realism now. When we watch a movie, we use the logic of every day to build the fictional world in our minds. Even in the world of Harry Potter the sun shines in the morning…. until it doesn’t. You see, being aware of the limits of realism and audience expectations can help you surprise them and raise questions. Lighting can become an important trigger for an audience to sense that something is wrong in a thriller, or deliver information that time has passed if the seasons changed.

This gets us closer to the actual objectives of lighting, which we’ll explore next time. If you're enjoying this journey, make sure to subscribe, leave a review, and join me next time as we keep exploring how filmmakers bring images—and stories—to life. If you have any thought, an example that wasn’t mentioned or a question, feel free to reach out—just email mailto:tal@cinematicimpact.com. You can also check out my book at TheLanguageofCinematography.com.

Thanks for spending time with me today. Goodbye!

Marlene Dietrich by George Hurrell

This is a transcript from Visium: The Secret Language of Images. Listen to the episode below:

Some years ago, I was on set filming a movie in Vietnam. This was a comedy, and the schedule was packed. We rushed from one location to another, doing our very best to finish days on time and get all the footage the director needs. If you’re an experienced filmmaker then you know, on set the schedule is the most important thing. And small problems tend to quickly become big ones if they cause even a slight delay.

In one particular day, we were about to wrap the day when the editor called to tell the director of a problem. Smart filmmakers start editing the film while its still being shot, because when you’re on set it’s relatively easy to squeeze in another shot. But once you’re done, getting that shot becomes the most difficult thing in the world.

Screengrab from De Hoi Tinh, directed by Charlie Nguyen and behind the scene image

The editor had an issue with a transition between scenes and a plot point that wasn’t entirely clear. He suggested that we quickly film the two main character running around in the street looking for a third character who has gone missing. Sounds simple enough, right? The only problem was that this scene was supposed to take pace during the day. It was already night, it was raining, and we were leaving to the countryside the next morning.

The producer looked at me. Can you create a day exterior scene, block the rain somehow and shoot this thing in 30 minutes? Like any ambitious cinematographer, I said yes first and worried about how later on.

Recreating daylight at night is not a technical problem. In the last episode we talked about the most important aspects of lighting: observation and language. So imagine yourself standing in a street corner during the day. Where’s the light coming from, and what is its quality? The difficulty in doing this exercise is that there’s actually more than one light source in a normal day situation. There’s the sun, but when the sun is not hitting the subject directly, it lights it indirectly through reflections from buildings, the ground and of course the biggest, softest light source we have - the sky. When thinking of daylight we have to separate all these different light sources so we can recreate daylight in a believable way - or to emulate it. Emulation is an important lighting word.

When I work with students in a studio and ask them to try and create daylight coming in through a window, they usually start by placing a lamp outside of the window as if it’s the sun. It makes sense, but it never looks believable. The difficulty is not related to lamps, it’s about understanding the quality of each light source. Once you know that, you’ll also be able to tell which lamp to choose.

So in Vietnam, I needed to recreate daylight outside, even though it was dark and rainy. I had flexibility with season and whether, the director just needed to get it done. So I decided to make it easy for the crew and myself - an overcast day, where the main light source is just the sky. We used all our largest frames with white fabric overhead, and bounced pretty much all of the lamps we had off the white reflector overhead. The result was a soft, even light coming from above, and as a bonus the frames also provided cover from the rain. This provided for a large enough area to use a wide lens, and that was it. The audience couldn’t tell.

This might sound extraordinary to inexperienced filmmakers, but if you’ve been making movies for a while then you have a story like this too. Filmmaking is a constant act of problem solving. When it comes to lighting, emulation begins with careful observation of every day light, and categorizing it in our heads using language. This was the only way I could quickly figure out how daylight looks like without using visual references, relying only on my experience and observation.

I’m Tal Lazar, and this is Visium—where we explore images and figure out what makes them work. In this first series, we’re focusing on the images you see in movies.

Who said you can’t learn lighting in a podcast? We’ve already covered some of the most important aspects of lighting, mainly its qualities and emulation. It’s true that as long it’s all in theory you are not really lighting, but remember that even if you’re not physically moving lamps you’re still designing. Choices like locations, time of day, or weather all affect lighting, and a director can easily participate in a non-technical conversation about lighting, looking at visual references to decide how lighting contributes to visual storytelling.

This is where we should mention something very important. If you look up cinematic lighting techniques online, you’ll find many guides and how-to videos. You’d learn about stuff like the three point lighting system or eye-lights, as if these are the methods professional cinematographers use to make their scenes look cinematic. I’ll say it in the most simple and direct way: this is a lie.

Lighting design begins when the screenwriter writes something like, interior night. A cinematographer reading that line immediately wonders where the light is coming from.

The concepts of key light, back light and fill light are important to know, but not for the reasons you might think. The idea that there is a technique to master that would just make an image appear cinematic should be insulting to directors and cinematographers alike. Think of some very successful films like Blair Witch Project, Napoleon Dynamite or the Dogme 95 films. You won’t find a lot of backlight there. The idea that there’s a shortcut to cinematic storytelling, that you can follow a convention and make the audience feel something and be interested, is just wrong.

The Three Point Lighting System

Sure, if you make something look like a movie, like my students say, you might catch the audience’s attention for a moment. But to keep them interested for the duration, you’ll actually need to tell a good story. So I suggest that you abandon the idea that lighting conventions are a path to learning cinematic lighting, and instead focus on what we talked about last episode. Observe lighting in reality and in movies, especially when you feel that it’s effective in making a moment powerful. Break it down using the basic qualities, and try to use it in your own scene.

But lighting conventions like the three point lighting can still be useful. If you’re not familiar with three point lighting, just look it up. Most of the lighting videos on YouTube teach you how to do it, because it’s much easier to teach a technical aspect of lighting than teaching people how to observe and remember. If lighting was so easy, all movies would look like a million dollars, right?

So how can these conventions still be useful? As a language. If you’ve ever been on a professional set, you heard the words key light, or fill light, endless times. That’s how the film crew communicates efficiently. A cinematographer might tell the gaffer that the contrast ratio is too high, and that more fill is needed. Contrast ratio is the relationship between the dark and bright side of the face. A 2:1 contrast ratio means that one side of the face is twice as bright than the other side. Adding fill means making the dark side brighter and reducing the contrast. But saying this means nothing about how it should usually be done, it’s just a form of communication.

The Blair Witch Project, directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez

Cinematographers and their crew speak in terms of key light, back light, fill light, foreground, background, separation and many other terms that all originate in conventions. Knowing these terms can help a director communicate as well, but no one should confuse these conventions with textbook methods to achieve storytelling effects. That requires context, which the story and the people working on it create.

Lighting design begins when the screenwriter writes something like, interior night. A cinematographer reading that line immediately wonders where the light is coming from. That question is rooted in a convention too, but a deeper one than three point lighting. You see, in the old days, filmmakers were not as concerned with the motivation behind lighting, where it comes from in the world of the movie. Old Hollywood movies, especially in the golden era, nurtured the image of its stars. Look at old movie still of Marlene Deitrich or Katharine Hepburn and you’ll see something interesting. No matter the scene, it could be in a dark cave in front of a firelight on the ground, and the light in a close-up would be a spot light from above, like a theater light. Maintaining the image of the star was more important than realistic lighting.

Contrast ratio is the ratio between the bright and dark side of the face

Today things are a bit different. The most terrifying thing for a young filmmaker is distracting their audience and reminding them that they are watching a movie. So every choice must be motivated by something within the fictional world, even lighting. That’s why cinematographers begin designing lighting by looking at the world. If it’s a night interior, then are there table lamps? Ceiling lamps? Candles? And if nothing, is there a window where moonlight can come in from? Lighting must have a reason to exist in modern conventional lighting, and if it doesn’t then there better be a good reason.

This convention is also a source of trouble, and why young filmmakers struggle on set with blocking. Not every angle looks good, and without understanding of lighting, actors and directors block scenes in a way that can make it difficult for an inexperienced cinematographer. Add to that a bit of insecurity and poor communication skills, and you got yourself a conflict.

So let’s try to settle this thing. First of all, it’s true that modern lighting conventions call for a sense of realism, but this is actually something a director and cinematographer should discuss in pre-production. Maintaining such strict realism while keeping a certain look means there are limitations in blocking the director should be aware of. More flexibility in blocking means also being a bit more flexible with the look, or developing it into something else. It’s really all part of the same thing, the style of the director is part of the storytelling.

Another interesting side to this expectation for realism is that it can very much be used in a creative way. Yes, the audience expects realism now. When we watch a movie, we use the logic of every day to build the fictional world in our minds. Even in the world of Harry Potter the sun shines in the morning…. until it doesn’t. You see, being aware of the limits of realism and audience expectations can help you surprise them and raise questions. Lighting can become an important trigger for an audience to sense that something is wrong in a thriller, or deliver information that time has passed if the seasons changed.

This gets us closer to the actual objectives of lighting, which we’ll explore next time. If you're enjoying this journey, make sure to subscribe, leave a review, and join me next time as we keep exploring how filmmakers bring images—and stories—to life. If you have any thought, an example that wasn’t mentioned or a question, feel free to reach out—just email mailto:tal@cinematicimpact.com. You can also check out my book at TheLanguageofCinematography.com.

Thanks for spending time with me today. Goodbye!

Marlene Dietrich by George Hurrell